Monday September 23rd 1940.

One can see it quite clearly now, autumn has already shown its face; the temperature has dropped, the leaves of the trees have changed their colours and a slight drizzle has descended upon this Canadian landscape. It will probably be only a few days now before we shall move into the huts which are nearing completion and leave the tents in which we have been housed during the summer months. A cool wind sweeps with biting effect through the grounds of the camp and suddenly the sun becomes visible from the slightly clouded sky smiling down onto the canvas town.

On the watchtower, which I can see from my tent, they are just changing the guards. In the last two weeks they have also installed a machine gun up there. That apparently is the regulation, although they know by now that we are only friendly aliens and not war prisoners. The barbed wire is electrified; that at least we were made to understand when we first arrived here two months ago. But for them it doesn't seem sufficient since they are always working on some improvements to ensure that there is no escape. Fifty paces from the outer barbed wire fence there is an embankment. Daily the trains roll by, and just now with a clattering noise like a death rattle, a train speeds by with its huge engine and the roar of its mounted, continuously ringing bell. In the street two girls are walking slowly along.

A car stops and the driver looks inquisitively out of the window into the camp. From the watchtower there are shouts and the car moves on. The two girls who were standing behind it are taking flight. Dolefully I am looking over to the embankment for some time after the hasty departing girls. And suddenly I feel transformed: I think of time passed, memories of past events come to my mind, of times remembered: when one was still "free".

"One thinks of Home", writes one of the five hundred internees in an essay, "Home, a sofa, a table with a lamp and its shade, books, records or perhaps a piano and a chair to sit on where mother waits on you with teacakes ...", as this young lad recalls. But there is more to it, there is freedom, liberty, where people have work, where people are joyful, lively and happy, where people love each other, where one can participate in affairs, be active, where there is life to the full - Freedom. But this freedom has now been taken from us.

We put up a long struggle to maintain this freedom and we were ready to participate in the great fight for the freedom of our land from tyranny, but we were rejected. Our friends misunderstood us, mistrusted us, and while Hitler's armies threatened the shores of England, panic stricken they have interned us and shipped us here to Canada.

On the 10th of May 1940 the announcer of the B.B.C Radio station reported that Nazi Germany had invaded Belgium and Holland and German aircraft with parachute troops were sweeping the sky and the invasion could not be halted.

It was morning, quite early; I had just finished milking the cows in the farm stable where I was working, when the farmer's wife entered breathlessly relating the radio report. The farmer and the cowman shook their heads in sorrow and anger; it concerned us all.

I stood there with clenched fists and my thoughts went to my cousin out there in Belgium who only three days ago wrote firmly believing that an assault by the German army could be successfully stopped.

"We are always too slow", said the cowman, cursing and swearing. "Let's hope", said I, "that things will take a turn for the better now that a new Cabinet has been formed with Mr. Churchill and Mr. Atlee at the helm and Great Britain has got a new ally".

"Much stricter measures will now be taken against all aliens", said the farmer's wife and advised me not to take my intended journey to Woking over the weekend where I was to visit a friend of my cousin who only recently returned from Antwerp where they had both been together.

In the evening we sat around the radio receiver listening to the latest news. They were still fighting; perhaps they may still succeed to beat the German army - perhaps. But didn't we say the same when a month before Germany occupied Denmark and Norway? Didn't we likewise sit around the wireless, listening, waiting - in vain? It was quiet in the small room where we were sitting together, and I told them the sad story of the Munchen betrayal. - Yes, indeed we also waited then, waited for something to happen, waited in vain.

In September 1938, when it seemed that war would break out any time, the people in the streets of Prague got very excited and were prepared - prepared to fight fascist onslaught of Nazi Germany.

Air raid shelters were hurriedly built, blackout was ordered, the whole city was covered in darkness. In the event of an attack it was anticipated, as was promised, that France, England and Russia would come to the aid of the Czechoslovak people and a war could be of short duration and Hitler and his armies defeated. Only in the outer zones of the country, the Sudetenland where the people were of German origin, would such an invasion have been welcomed. For them, their hope was aroused to be "free" and integrated into Nazi Germany.

On the 11th September 1938, the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, decided to fly to Berchtesgaden in Germany to confer with Adolf Hitler in the hope that a war could be averted and to reach some sort of compromise. But in the German newspapers and on radio, the war of nerves against the people of Czechoslovakia was intensified, the Czechs called beasts, oppressors of the German population of the Sudetenland which, they said, was German soil and would have to be ceded to them. There was no compromise to. be had with the bloodthirsty Fuhrer who only in March of the same year marched into Austria and occupied the land. Everything pointed to a declaration of war.

The Czechs were ready and it seemed France, England and even Russia would be standing by as allies. The Czech Government was informed of their promised help, and a general mobilisation was ordered. With an enthusiasm as I have never seen before, the Czech people took to the streets that same evening, their cases packed. Cars were ready to take them to the railway stations where the first trains were prepared to leave with the new recruits. The Czech people were ready to fight the war for Freedom, to fight the war against Hitler's Fascism; for them the war had already begun. Suddenly, however, they were disillusioned.

Once again Mr. Chamberlain left for Munchen on 29th September and together with Monsieur Daladier, the then French head of state, accepted Hitler's ultimatum that the border country of Czechoslovakia, the Sudetenland, should be integrated into the German Third Reich. The status of the Czech people would be recognised. - "Peace in our time", those were the words of the British Prime Minister when he returned home. - Czechoslovakia was sold out.

The lights went on again, the soldiers disbanded and with tears in their eyes, the Czech people went home again, downhearted, because they knew it was wrong and they could not fight alone. On 1st October, German troops marched into the Sudetenland and the Nazis immediately took possession of the various Council Offices in that area. The Czech Government resigned and a newly formed government, more friendly disposed towards the German regime, took office.

The promise given to the British Prime Minister in Munich that the status of the Czech people would be recognised, was broken and on the 15th March 1939 the Nazis occupied the rest of the country. At 9am the German troops reached Prague and soon afterwards the Government departments, their administration and radio stations were taken over. By 11 o'clock the Gestapo made their first arrests.

That was the Czechoslovak betrayal, that was the policy of Munich which separated thousands of children from their parents and parents from their children. Another exodus had begun - 5000 refugees.

I don't know whether the family sitting there understood all I was telling them. I don't know whether they were actually aware of this new situation, the threat to their own shores. The farmer sat there in reflection and then he said "We'll beat them!”

Next day, on the 11th May, I am standing at Woking railway station, looking and waiting. Where is Gertrude? Actually, I do not know her yet. Three weeks ago she sent me a snapshot photograph of herself, and her letters were a comfort to me. My cousin over there in Belgium had asked her to contact me and now I was to meet her.

“Oh hello, here you are." A nice, rather plump girl leading a bicycle comes towards me and introduces herself. As I look at her, she says “I expect you must be disappointed to see such a fat girl. I never used to be like this but being engaged as a cook, it is hardly surprising." "There is no need to apologise; you look just fine and it has no bearing on our meeting".

We then walk through the park and she tells me how she managed to come to England, obtaining a permit as a domestic servant and then procured employment as a cook in this district. - “My fiancé is still in Antwerp, we are engaged to be married and now I am afraid that we shall be parted for ever. “ I wonder what is going to happen to my cousin out there. Will she be able to get away?

Gertrude, reading my thought, says, "With a bit of luck your cousin and my fiancé could still make it somehow. - Your cousin actually told me all about yourself and the kind of love affair you had with a girl and the sad end of it. Perhaps I could console you and give you some advice ."

How strange, I think. - I really fell in love with a girl and we nearly got married but for an incident which prevented it, and it all came so suddenly. It was 'I' who was hurt and now Gertrude tells me that it was a lesson to be learned from the experience.

"I know", she says, "it must have been a great disappointment for you, but walk tall and try to forget. The day will come when you will find the right partner. For the present, concentrate on your work".

“How right she is", I say to myself. And only a few days ago Herman wrote to me, he also telling me to forget this affair. I feel quite ashamed - and suddenly I am transported back there in Prague.

I am standing on the platform of the Railway station, my parents are there to see me off, and somehow there is a feeling that I shall never see them again. My mother cannot hold her tears back and I plead with her to constrain herself as she could draw the attention of the Gestapo men who are there observing the passengers, perhaps to discover whether some are taking the journey to flee the country.

After a last good bye I board the train, and as it slowly rolls out of the station, a last wave from the window till the train winds itself like a snake into a curve along the rails, gathering speed.

A last view of the lovely city - there is Hradcany Castle and the Charles Stone Bridge, there Carline, the district where not so long ago I had worked in one of the printing works, and in the distance I can see, our house.

A last look. I never would have thought that the Nazis would come this way to capture that strong bastion of democracy. Here I thought I would be safe.

Everybody thought it could never happen here, and it need not have happened. And once again I take the road into the unknown, away from the Nazis, to escape from the clutches of the Gestapo.

Forgotten is the incident with the girl, forgotten the little love affair, forgotten the kind Gertrude sitting here listening as my thoughts dwell on the night after the train reached its destination: Moravska Ostrava, the border town.

Alighting from the train as darkness falls, I and my two companions are taking to the surrounding hills, into the woods to cross the border unseen to safety into Poland. It was the 2lst April, Hitler's birthday, and we thought this to be the best opportunity to try to cross the border with guards and people celebrating the occasion, not being too alert to notice any illegal movements.

A searchlight from the near road beams across our path and all three of us hurl ourselves to the ground into a nearby ditch. We are wandering for three hours through the dense forest up and down the hills towards the border.

The glimmering ashes of a coal mine become visible and we are approaching the small village with its rows of workmen's houses. Dogs are barking and in the distance someone fires a shot. We are taking the plunge; it is past midnight and there is still light in one of the houses.

We knock at the door. After a while a working woman with a frightened look on her face opens up and after explaining our plight, hesitating at first, she lets us in. The state of our muddy clothes can now be seen in the light. The woman and her husband and the two children who are not yet asleep are very kind to us, and after a brush and a clean-up and a hot drink of coffee we fall asleep around the kitchen table.

At five o'clock in the morning we are awakened by the kind couple who gave us refuge, the man showing us which road to take out of this village. At dawn we make our way amongst the miners who are on their way to work in the pit. At last we manage to escape further from the still menacing border guards, and after some more helping hands from sympathetic polish people, we board a bus to the town of Catovice.

"How did you board the bus to Catovice?", asked Gertrude. "We didn't actually board a bus to Catovice straight away", I replied

After we left the little house where we were given shelter and joined the stream of workers, we were confronted by a man whom we thought to be a Gestapo and already saw ourselves behind bars in prison. "You just crossed the border”, the man said. "I want to help you because you are already observed by the border guards over there. Just follow me and keep walking".

We walked a few hundred yards till we came to a crossroad where this kind man showed us where we should get the bus due in half an hour to Frystadt. We thought ourselves lucky to have found such a person, and I gladly gave him the few Czech cigarettes I still had.

Adler, the name of one of my two companions, wanted to go into the centre of the village and see if we could get a train straight to Catovice. However, it was safer just to wait for the bus, and we were supposed to make contact in Frystadt to be helped along from there. Eventually the bus came and we had no difficulties to get on it.

In Frystadt we went to the inn opposite the bus stop, the address given to us in Prague, and we asked for the proprietor who took us upstairs into a hotel room to wait. After a while the Rabbi came along, asking questions and saying that there were already thirty people in prison, arrested for crossing the border.

He left, and more people came, wanting to know what it was like under Nazi occupation. The Rabbi returned shortly with money collected for the fare to Catovice, and he took us to the square where a coach was just about to leave.

Armed with a Polish newspaper which we couldn't read, we boarded the coach, waving good bye and thanking the Rabbi for helping us.

It was late afternoon when we arrived in Catovice where we received shelter and refuge and considered ourselves very lucky to be alive.

Gertrude listened with perceptible sympathy to my story and both of us felt that here in England we seemed to be quite safe. Now that the war was in full swing, it was obvious to us that the Nazis would be beaten. We would have to do OUR share and enrol and work with the British Army and people, work in industry and on the farms. We were the lucky ones to escape from the clutches of the beastly Nazis and their concentration camps. As refugees from Nazi oppression and as friendly aliens we were now in this fight together.

Strengthened and resolute from the memory of these events and adventures and the meeting with that spirited girl Gertrude, with her courage and cheerfulness, I returned to the farm. The red golden ball of the sun dwindled slowly behind the hilly fields in the distance, and as I looked at it for a long time, I resolved to begin afresh, to forget the past and if I must, join the corps, the forces in which Rudi and Fred have already enrolled. They were happy to join up - and it was quite fun when I tried Rudi's Army coat on before his departure. But one must not be sentimental about it. For us the duty is: to work.

Sunday 12th May, Whitsunday, 1940.

Out of the blue sky the sun in brilliant splendour radiates down onto the landscape. The cows have been milked and are grazing in the meadow, the work is completed for Sunday morning. I walk along the field still enveloped in my thoughts of yesterday's encounter with that courageous girl. The farmer's children come jumping and dancing joyfully towards me and I am glad to be here with those happy-go-lucky questioning little mites. It is time for lunch and all sit round the table enjoying the Sunday roast. Just as the dinner is finished, the dishes cleared away, there is a knock at the door.

"Someone to see you", says the farmer, pointing at me as he entered the room. Whoever would want to come and see me? Out in the forecourt there is a car, and a man with an artificially friendly smile comes towards me. "Mr. Pollak?" “Yes sir". What could this man possibly want from me? ''Mr. Ernest Pollak?" "Yes". "What is your age?" "Twenty-four. - Why do you ask and what is it you want?" "You are requested to accompany me to the Police Station for an inquiry". I notice a police constable getting out of the car and waiting there. "Surely it must be a mistake. I have already been before the Aliens' Tribunal and my classification 'C' gives proof of my being a refugee from Nazi oppression. I am considered a 'friendly alien'. Here is my registration book". "Yes, we do know of it and that is quite correct. This is only a formality and you have nothing to fear. You'll be OK", says the detective. "You don't have to take anything with you, just the gas mask, a couple of shirts perhaps - no need to take a towel. That will do". "It Is all so strange. Surely it can't be right. I expect I shall be back later today", I say to the farmer apologetically. "Don't worry", he says. “Circumstances, you know".

A few minutes later the car stops at another farmhouse and after a short while another young man of about 28 years joins me in the car. So it goes on - a third, a fourth, a fifth. We all sit in the car, cramped together, eventually reaching the police station in Aldershot after a 45 minutes journey. In a large room there are already 8 people waiting, all looking anxious and inquisitive, all being in the same position. Eventually more young chaps are brought in and the number in the hall totals 16.

We are then asked to mount a lorry with a police officer and three soldiers guarding us. There are sixteen of us in a wooden hut guarded by soldiers. Opposite the hut is a Prisoner of War camp surrounded by barbed wire with prisoners, German soldiers and sailors, obviously Nazis. The British guards in our hut are astonished by the fluency of our spoken English, and after explaining to them our position that we are far from being Nazis or German prisoners, they comfort us, insisting that our presence here is only a "temporary measure". "From what you have told us, we are convinced you will be released soon", says the sergeant, and he produces a newspaper from his pocket where we read all about "The Great Round Up". The Government is trying to learn a lesson from the invasion of Belgium and Holland by German paratroops and the so called "Fifth Column", therefore, the internment of all aliens irrespective of their status has been ordered. I am told that the farm where I work and live also happens to be in a protected area, a military zone in which movement is restricted in any case.

Hours go by, days go by. We are not allowed to communicate or write letters. What about the personal belongings and clothing we have left behind? The answer to our question is always the same: Sorry, there is a war on. A German naval rating from across the camp accompanied by a British soldier brings our meals, nothing but beans and rice, rice and beans, and bread, and the coffee is not drinkable. The little money we still possess is soon running out from supplementing our meals with ham rolls and chocolate which the soldiers buy for us from the village store. “England is finished; we've already won the war", says the German sailor. We just laugh in his face, and the prisoner is soon escorted back to his camp from which their Nazi songs penetrate into our hut, to our annoyance.

Behind the hut is a small field where we are allowed to take exercise, stretch our legs walking backwards and forwards, up and down, guarded by eight soldiers, equally spaced out along the line. One hour in the morning and one hour in the afternoon, day in day out. There are two youngsters amongst us who have lived all their lives in England although born in Germany. They still hold German citizenship because of an oversight by their parents not having been naturalized; therefore they also have been rounded up. Even the German sailor bringing our meals shakes his head in astonishment on hearing this. We sit on our hard beds with their bare springs and no padding, reading, talking or playing cards. It is all so strange. Perhaps one more week and then we go back to our work.

Another anxious four weeks was the time in Catovice when I waited and waited for the transport to England.

I daily visited the British Vice Consulate where I was interviewed and selected as one of the deserving cases from the many hundreds of people in the same plight. I was lucky to be on the next transport, and soon I was on board the ship to England.

The night before the departure, Adler, Kroner and I went to celebrate the event, Adler mentioned to the girl who served us that I would be on my way to England the next day. Hilda had actually just finished her work and we had a nice chat. She told me she was sorry I was to depart the next day. The train was not leaving until just before midnight. "Someone to see you", I was told, and there was Hilda on the platform to see me off. I was pleased and also thought it a good omen.

The special train with its load of refugees moved along the track, and it was early morning when we reached the port of Gdynia where we embarked on the liner 'Castleholm' for Stockholm in Sweden. To avoid passing through German waters, a ·train took us from Stockholm to the port of Gothenburg. Speeding through the Swedish countryside with its green fields, lakes, buildings, rushing through villages and towns, it was as if the wheels touching the rails shouted: "You can't stay here!" At the harbour of Gothenburg a ship was already waiting to take us on the last lap to England.

It was late afternoon when we landed at Tilbury. We passed through custom - most of us only had a few shirts and underpants. 'Anything to declare?' It was a laugh. The passports were stamped: Leave to land on the condition that the holder will emigrate from the U.K. and will not take any employment or engage in any business, profession or occupation in the U .K. - Leave to land granted 22.5.1939. We were in England.

How the heart was beating fast, jumping for joy, the eyes grew big seeing the sights of London from the top of the bus for the first time - Whitehall, Houses of Parliament, Westminster Abbey, Buckingham Palace. We were here at last After the first accommodation provided in a large school hall, the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia had arranged to house some of us at various places and resorts in the country.

I found myself at the seaside resort of Ramsgate which was to be our new home. An obsolete hotel along the seafront was converted into a hostel and there, interwoven into a community of thirty six people, German and Austrian Refugees, we were to live free from all dangers again. There were three married couples amongst us, and. we soon became used to the existence derived from the Munich Policy of 1938.

A vast sum of money was put at the disposal of the then formed committee to promote this emigration policy, and this hostel was one of many such establishments in the country: My window looks over the beach and admiring the sea view, watching the tide, the waves beating against the sandy shore, I feel an overwhelming sense of relieved excitement.

It is a wonderful feeling sunbathing on the sandy beach, swimming in the sea and enjoying the movements of the waves swaying backwards and forwards, up and down. It is early summer now, many people feel the pleasure of their holiday in the sun. Children are building sand castles. Seated around us are good looking English girls. We soon make friends and in the evenings amongst the coloured lights we walk along the promenade to the tune of 'The Umbrella Man'. With music all around us we feel like being transformed in an enchanted land of splendour.

There is also work. We are to convert a derelict building into a habitable hostel for elderly refugees. The English people are very friendly and sympathetic to our cause. One makes friends with an English girl and even falls in love. To be independent of the Committee one tries to get other work, but work is scarce.

The news is not very good. Poland is invaded by Nazi Germany. Catovice, the town to which I, with such effort and trouble, first escaped, which gave me sanctuary and enabled me to come to England, is now heavily bombarded. We sit around the radio listening to the latest news: Krakow besieged, Warsaw taken.

On 3rd September Chamberlain declares war on Germany. Sirens screech with devastating sound through the air. The lights go out. Everybody rushes to the air-raid shelters. Gas masks are issued, and very soon the first German plane appears in the sky. In the Underground Cliff Railway, used as an air-raid shelter, people assemble for safety from the first machine gun fire from the German aircraft.

The next day we all have to go to Margate where the tribunal is in session to establish the reliability of aliens. We all pass as friendly aliens being refugees from Nazi oppression. Rudi and Fred join the Pioneer Corps. The Committee calls for volunteers for industries and on the land. 'Dig for Victory'; England needs you!

I write to Herman about the farm situated in that peaceful countryside where the war seems remote. There are twenty of us young people accommodated in a large farmhouse with a 300 acre farm nearby. We learn to milk cows, clean stables, groom the horses, attend to chickens and pigs, doing field work and gardening and find it fun to drive the tractor which is very often found stuck in the hedge. After three months one is quite experienced and then you can leave for a real job as a farmhand.

Perhaps I would not have been interned had I remained on the training farm? What did the farmer really think? Has he really understood what I have told him?

The Camp Commander enters the hut. Are we at last going to be released for our work?

The conditions in the camp hut deteriorates. No post - no newspapers. It is eleven days now since we came here.

At five o'clock next morning we are woken up. We are given one hour to get ready. A truck takes us to the railway station. Where are we going this time? To another tribunal in London perhaps? After one hour's journey, at Waterloo Station special buses take us to board a train at Euston Station. The compartment of that LMS railway carriage is quite comfortable. Flanked by soldiers with their rifles shouldered we sit there with puzzled looks wondering about the journey and the train's destination.

A sergeant appears in the door- way, shouting at me: "What are you looking at?!" "Don't shout at me", I bellow back at him. "I am not a prisoner of war or a criminal". To which with a contemptuous look as he moves on he shouts: "Shut up, you". One of the soldiers, friendly disposed towards us, tries to calm me down: "Please don't make a fuss, let him be".

The train moves along and at a station it stops - Rugby. German prisoners of war from the front carriage of the train are escorted out along the platform. No information is to be had from our guards, they themselves are unable to buy a newspaper.

Eventually the train again comes to a halt - Liverpool. "All change!" At the opposite platform we step into another train already waiting and labelled 'Occupied by Military Personnel'. How much longer? We could do with a meal, having been without food all day. After a short journey of twenty minutes we arrive at the small town of Huyton.

At a first glance as the bus approaches the gates of a huge camp [1] fenced by barbed wire it occurs to us that we are now in a prisoner- of-war camp like the one we saw from our hut back there in Ascot. "Come on, move along!" In a big marquee we are seated and given tea, bread and marge and jam. There are already many others here, young and old, people with long beards, Jews, Gentiles, people of various nationalities - Germans, Austrians, Czechs, Poles. "Is there enough to eat here?", I ask one of the bystanders. "We have only been here for four days ourselves". New groups arrive in a constant flow. Alfred shakes his head in disgust, Otto says "Man, this is Dachau".

I hear my name called, and as I look round there is Walter from Ramsgate. So they have rounded them up too. "Are there any others from the hostel?" At that moment Josef and Herman turn up. "We are all here - when and where did they get you?" So they are ALL here. How strange. We are shown to our quarters.

A small estate with buildings surrounded by small gardens becomes visible. A little village which we at first had not noticed has been made into a huge internment camp. Barbed wire with watch towers round it has been erected here - Shepton Road, Belton Road, Pennard Avenue, Altmoor Road. There is actually a post office and shops. Headquarters: Belton Road No 27.

How many acquaintances one meets! Acquaintances from Vienna, from Prague! "How long have you been in England - when did you come - what work were you doing?" Questions, astonishment, more questions. At 37 Shepton Road where the friends from Ramsgate are billeted, there is room for three more. Alfred, Toni and myself take the room on the ground floor, one in each corner of the room on a straw mattress.

There are already 3000 of us here. With plenty of space, one can at least walk through the streets. Our documents and the new possessions have to be surrendered. All have to undergo medical examinations. At first one is unaware of the actual fence till the sentry calls out: "Keep away here - six feet from the wire!" Soldiers still pace the streets with shouldered rifles.

As on the February days of 1934 in Vienna, the stormy days when martial law was proclaimed and a curfew imposed! It was there it all began! Parliament was dissolved, democracy was wholly suppressed, its defenders imprisoned or sent to concentration camps, dictatorship became fully fledged; Civil War was on. Vienna's modern tenement buildings of the Karl Marx Hof, Goethe Hof, Lassalle Hof and all the others were turned into fortresses where desperate fighters for democracy tried to defend themselves against the new onslaught of fascism. Thousands died. They found sympathy all over the world but again no active support was forthcoming. It was the first battle against fascism in Europe, forerunner of the undying glory of Madrid in 1937, the Spanish civil war, and of Warsaw in 1939.

I meet Maurice with whom I worked at the Evening Institute in Vienna. The picture of the Vienna Woods, the Danube, Saint Stephen's Cathedral, the Prater, of times gone by, take shape again. So Maurice too was able to get out in time. Who would have thought it possible? ''Herta is in England", I inform him. "Yes, I know", he says, "her brother has been taken to the Dachau Concentration Camp!", Who would have thought to find oneself interned here?

Letter forms are issued. At last an opportunity to write, to communicate. My first letter goes to the farmer asking him to forward my belongings. What did the police inspector say back there on the farm? - Only a few hours. - I wonder whether Joan will send me a food parcel? Only two days before my internment she wrote to me inviting me to come to Cardiff for a holiday. Jessie, too, would send me a parcel, the fiery Scottish girl from Glasgow who always sent me books to read when I was in Ramsgate. - Will I receive a letter from my parents who are still back there in Prague? I wonder if they are still free or maybe already in some concentration camp?

The camp fills up and daily there are new arrivals and more acquaintances. 7000 now! A kind of camp university is being formed with courses in English, agriculture, economics and many other subjects.

A food parcel arrives from Joan, another from Jessie, Herta and Ricka - good old friends. I wonder what has happened to Gertrude? Is she still in Woking? Alfred receives a parcel from his wife, and Leopold's sister actually sent him some rye bread.

We make ourselves at home, build some primitive tables from scrap wood, and Tony has even got a typewriter so we can type our applications for release from internment to· the Undersecretary of State at the Home Office. 2000 internees are sent to the Isle of Man. Alfred and I are on the transfer list too, but we evade the departure and remain in the camp. I work in the post office sorting and delivering letters and parcels within the camp, for which we receive extra provisions of bread and cheese and coffee to supplement our ration.

On the parade ground a concert is in full swing, the band formed by the internees and directed by the quite well known composer Franz May: "Don't worry after bed time, Although there is a sad time, Let music play, let cheerful music play!" Like a balmy soothing effect on the gloomy, dejected community, the sound penetrates all over the camp to the delight of the internees. Small groups form themselves as entertainers, singing, acting, dancing and the like. Even the soldiers in their barracks and the village population outside the fence enjoy to some extent the entertainment provided. But apparently no such 'fraternisation' is allowed and the order goes out that all such activities must take place at the distance of at least thirty feet from the wire fence.

Rumour has it that the Germans have occupied Paris and are making headway to the French coast. This is later confirmed by the Camp Commander. The camp looks nearly half empty after the departure of the 2000 internees to the Isle of Man, but they are soon replaced by Italians. Those who have relatives living in England are now allowed to be visited, and from them we can get information and news of events. At mealtimes there· is now also a news bulletin read out every day.

New arrivals enter the camp and more friends and acquaintances turn up. There is Karl! An old friend from Vienna. What a fascinating story he has to tell! He was in Luxembourg , then in Belgium. Twice he tried to stow away to England till eventually he succeeded in spite of strict measures and guards all round. Hurled in the ships coal bunker he hoped to reach his destination, England, undetected. At 3am the boat docked at London Bridge. He managed to disembark unseen and eventually find his way to his sister who had been living in London for some time. He was imprisoned for illegal entry but after a while appeared before a tribunal and was set free as a 'friendly alien'. The Committee helped him along and now the gate of this vast camp has swallowed him up.

Johann who was in Prague and also worked for the Committee in London is here too. He has some more news for us: Glaser and his wife were able to emigrate to Canada and have been given £200 in settlement money. Lucky devils!

A letter from Rudolf arrives from France. Army life seems to suit him, the wine is good, the girls are sweet. No. 3 Company .AMPC. Aux. SVCE BEF. This letter was written weeks ago and I wonder where he is now since France has been overrun. I hope the Germans have not got hold of him. Oh Rudi! He had some adventures behind him!

In 1927 he left Vienna to serve-in the Czech Army where he had been called up, being of Czech nationality. His military service completed, he returned to Vienna and in 1934 found himself amongst the freedom fighters after the overthrow of the democratic government there.

Again he was compelled to flee the country, and it was not long before he enrolled in the International Brigade fighting in Spain where the Spanish Civil War was raging. Si Senore - there he was in Barcelona and Madrid, fighting in the mountain range of the Pyrenees together with Swedish, Dutch, French and English brigades, practically all nationalities. And all of them fighting in that International Brigade against Franco's Fascism side by side with their Spanish brothers. Thousands died a horrible death from bombs and poison gas. Rudi found himself in hospital, having been wounded.

He returned to Czechoslovakia and realized that the Spanish Civil War was the rehearsal for the great war to come, after finding himself again on the German frontier. In 1939 his life was endangered by the threatening Nazi Germans, and he just managed to cross the border into Poland and arriving in Catovice he was finally brought to England by the Czech Refugee Committee. - I shall never forget that evening on the beach by the glimmer of the coloured lights when Rudi related the story to us.

New rumours are spreading through the camp: Everyone is going to be moved on. Tony and I sit with our typewriter compiling a list for the so called 'Brazil Action', a project whereby the possibility is sought to obtain a permit for emigration to that country and so secure release from internment. At that moment we are asked to report to the house-father who informs us that we must pack our bags immediately as we are going to be transferred to another camp early next morning. The destination is not known but one's luggage must not exceed 20 lbs in weight and put into the provided labelled sacks.

There is great excitement and questions remain unanswered. Edi thinks we are going to be sent to Wales, another knows it is Scotland, perhaps Ireland, but the majority are convinced it will be the Isle of Man again. Some, however, believe we are going to be shipped to Canada. It is known that 50 of the Italian internees left last Sunday at short notice, and it is rumoured that they were sent to Canada, although they were not friendly aliens but Nazis or at least Nazi sympathisers.

I make my way to have my luggage weighed and it looks like being less than 10 lbs. Karl and Johann are already there with their small belongings. Alfred tries to dissuade me from going and thinks I should stay behind as I did at the time of the first Isle of Man transport. But I am resolved to go this time. "I hope you don't regret it", he says. I take leave from my friends. "Good luck, all the best!" - In my pocket I find a bar of chocolate and some meat paste which Alfred has put there while I wasn't looking.

On 3rd July at 6 o'clock in the morning we sit along the long table in the large marquee eating our last breakfast. The gates open and flanked by the soldiers we are on our way to Huyton Railway Station once again. Alfred, Leopold and Walter wave again. One last look back at the Aliens Camp[2] - goodbye Shepton Road, Belton Road, Altmoor Road, Pennard Avenue.

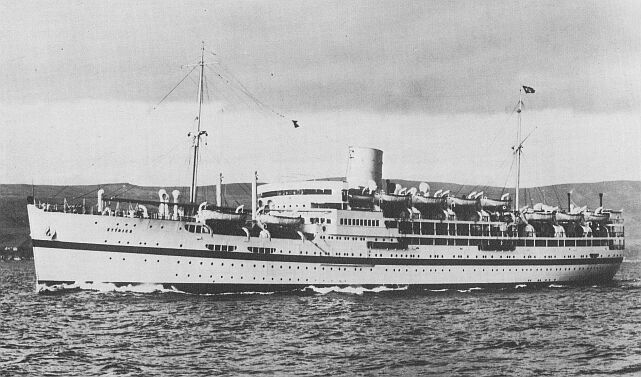

From the quay at Liverpool harbour we notice three ships, one an ocean liner and two smaller boats. Everyone knows that if we embark on the larger vessel it is destined for Canada, the small boats for the Isle of Man. Order goes out to hand in all gas masks and then we board the 9000 ton liner M.S. Ettrick.

We find ourselves tightly pressed together on the lower deck which is fenced off by barbed wire. On the other side of the large boat there are German Prisoners of War, Nazis in their uniforms, their Nazi songs loudly ringing in our ears.

At 5pm the boat at last begins its passage across the wide sea into the Atlantic Ocean, and one becomes aware of its rocking movements. Seated at large tables we are given fried bacon, bread, cheese and tea - in fact quite a good bit to eat and it goes down very well. Life belts and hammocks are issued and, in spite of the ship having been converted into a troop ship, the overcrowded boat does not leave much space to spare. People sleep on tables, on the floor and even on the small staircase. I feel quite comfortable in my hammock, hanging up there in the air. Somebody is sea sick and others are soon affected by it and the smell becomes abhorrent. I too feel faint and keep close to the ventilator. - Only not to be sea sick - to sleep - not to think - to sleep Does it really go to Canada?

Yesterday I received a letter from Jessie - she had heard from Rudi who managed to get back to England and is now in Devon.

Our luggage is on the upper deck and with it our towels, razors and the other toiletries. Perhaps we are only going to Ireland and will disembark again tomorrow I wonder where mother and father are now and how they are faring? Damn this war! I wonder what they would say if they knew of my being on my way to Canada, North America? Will there be another tribunal, another camp, will there be work? The head swirls round with thousands of questions, not knowing any answers.

The next morning from the corridor behind the barbed wire the sea becomes visible and the swaying of the boat is more apparent. We can see clearly the distinctions and ranks of the German soldiers on the other side of the barbed wire fence. Their songs 'Today Germany belongs to us, tomorrow the whole world', is countered with our English songs, 'Roll out the barrel ... It's a long way to Tipperary... My Bonnie lies over the ocean'.

The coastline slowly dissolves on the horizon and before us is just the ocean, the vast mass of sea water. We can now move to the other decks where the other groups from the Isle of Man are. Willie is there, the old school friend from Vienna! We have known each other since we were six years old, and we sit here reminiscing about our schoolday antics when we teased the teachers and many times ended up reprimanded. - Fancy meeting Willie here.

Seasickness amongst the passengers is on the increase. Up and down - the rocking ship plods on. The sick-bay on the ship is crowded with people in need of attention and treatment. Apart from seasickness, diarrhoea has taken its toll of a number of people, and I too find myself queuing for medicine to alleviate this uncomfortable state. Behind the wire soldiers parade with their shouldered rifles along the corridor. Some of them are also seasick, and the military police pace up and down through the crowd. Someone is taken to the sick-bay, unconscious - "Gang-way - sick man!"

As in a mirror in the blue sky the sun reflects itself in the large sea, now very calm, the ship just floating along. Just as it was on the steamer 'Castleholm' in the North Sea on the journey to England - just as it was down there by the harbour at Ramsgate, the calm sea, the blue sky, observing the slow current of the sea waves embracing the sandy shore.

Joan walked alongside me on the promenade. "Is your country by the sea?" "No, where I come from there are just lakes. This is the first time for me on the beach by the sea". Then I told her all about Austria, Vienna, the Danube, the Vienna Woods, the many lakes, the mountain range of the Alps, about Czechoslovakia, the river Moldau and Prague, its capital city. "This is only the English Channel", she said. "You should see the sea at Southampton, the ocean where the waves with undulatory movements swing high up in the air and carry the great liners across the world".

And here I am now on the great boat, though it is only a troop ship travelling on that great ocean, and over there is America, Canada. Good bye Europe! Good bye Joan!

And I wonder what happened to Violet, the other girl I fell in love with in Ramsgate? Violet, the girl who nearly changed the direction of my life - a love affair - a broken heart. All in the past now. Absorbed in my thoughts I suddenly feel a hand on my shoulder. Turning round, thinking my eyes are deceiving me, I come face to face with Franz who was in Ramsgate with me - we both fell in love with the same girl. So they got him too! Taken from his place of work, shipped to the Isle of Man, he is here with us and all the other internees on the prisoner-of-war ship Ettrik. Is it fate that we both meet again?

"My thoughts were back there in Ramsgate when you poked me on the shoulder just now", I say to him. ''Isn't it strange, Franz, do you remember the wonderful evenings we spent together with all those girls? And then came Violet - it shouldn't have happened". I am so glad that we have come face to face again - are you still my friend?" says Franz. "Now tell me the truth of what happened". I give an account of all the incidents after he left Ramsgate to work on a farm.

How I wished I'd never met the girl, how I doubted her sincerity, how it was she who pleaded her love for me. "If you don't love me any more I shall die", she had said to me. "I'm expecting a baby in August”. This had come to me like a bombshell and I asked her outright: is it Franz' baby?" "Of course not", she had said, and how could I ask such a question, and she seemed upset.

"Shortly afterwards", I say to Franz, "as you well know, I left for the training-farm and we corresponded with each other.At the end of March a letter had arrived from Violet's mother to tell me that Violet had been ill and only that day she was told of her pregnancy, and since she didn't suspect anything, it came as a great shock to her. She suggested that I came to Ramsgate as soon as possible to sign at the Registry Office to be quietly married. Knowing that it wouldn't be possible for us to live together for the time being, she would give every support until a time in the future when I would be able to keep her. "

"In my reply to Violet's mother I gave an account of her not having been told by her daughter of the expected baby whereby she insisted on keeping it quiet and said that an aunt of hers would be willing to adopt the baby. I also wrote to Violet expressing my doubts of all this. However, I was eventually persuaded to go to the Registry Office, and the wedding was to be on 26th April.”

On the 20th April I received another letter from Violet's mother which eventually changed everything: “...Violet's ordeal came swift and suddenly, but she is quite well. A little girl has been born prematurely. We were at the pictures. All plans must now be altered. I have postponed the wedding and your permit to come will hold good ..."

I immediately wrote back, pointing out that since I had known Violet only six months at the most and was under the impression that the baby would not be born until August or September, I could not accept that this was a premature birth and it was therefore impossible for me to be the father of the baby.

The next letter was to the point, and I felt there was a deliberate deception, not only by Violet but also by her mother: "Violet will write you a long letter this week. My Dear, my brain does not seem to work any longer and I think it better to leave everything entirely between you and Violet. After last Saturday's air raid, whatever happens, I shall try to get away immediately Violet can travel. I am saying nothing, because now I have no voice whatsoever in the matter. “

The following day I was on my way to Ramsgate, the hostel could accommodate me and I met some of my old friends again. Herman said "You can't go along with that deception, you have to think of your future". I suddenly realised what actually had happened. I felt cheated, hurt, humiliated and a sudden spite for the girl.

The next day when I saw Violet and her mother, it became quite clear to me that they knew all along about the tragic affair, and it became evident that I had nearly fallen into a trap! I explained to Violet that under the circumstances a marriage wouldn't be possible and wouldn't work. We parted with no ill feelings, "Lots of luck, Violet. Let me hear from you sometime." With scornful looks the mother turned on me, saying “I know that Franz would have married my daughter whatever the situation."

Here Franz smiles and says "I hope you don't think that I was the father of that wretched baby? I more or less heard about it, though I didn't know it all. As far as I heard they are in London now."

"Franz", I say, ''I hope you do understand it all better now. I was hurt and yet I was lucky. Herman once said sometimes one has to think of one's own existence, one has to be a bit egoistic."

"Yes", says Franz, "quite true. One has to be like this sometimes. Strange, really, one comes to England, a refugee, and the women are on the look-out to find some victim, so to say.”

"And they picked on me", I say, "or shall I say picked on us, and nearly succeeded. Well, it's all over now, indeed, all over now. I suffered enough, believe me. My cousin and Gertrude did a great deal to console me in my trouble. And then they interned us - here we are together, not even knowing where we are going. It could even be the Devil's Isles".

Franz is quiet, then looks at me and says: “That is all in the past now, we still remain good friends!"

Johann is seasick and vomits persistently. I begin to feel faint and also rather hungry and long for something to eat. Someone is selling chocolates he has obtained from the soldier's canteen, 3d for a small piece, and he profits by ½d At last, after ten hours, we are getting a meal. There are two meals a day now - 8 in the morning and 6 in the evening. Representation is made to the Commanding Officer and then we are issued with two extra biscuits a day and allowed on the upper deck for two hours.

Our luggage is still withheld. I am pleased I put my razor in my pocket when we left Huyton.

The freshly baked bread on board ship is still warm when we eat it and it causes stomach upsets. I am awake in my hammock with abdominal pains. There are five buckets on top of the steps. The door is locked at night. All the buckets are in constant demand, the smell with its strong bad odour penetrates the nostrils and wraps itself around the overcrowded room. It seems a very long night, and when at last the door is opened at dawn, the continuous rush and queue to the latrines does not alleviate the sickening situation.

Franz is in the sick-bay with a high temperature and constant vomiting. Complaint is made to the Colonel about the intolerable conditions within the compound of the ship behind the wire fence. At this the Colonel becomes agitated and retorts: "You are nobody!” The machine guns on the upper deck could also be turned against US if need be. The complainant is then taken to the cells below. The soldiers recognise our status and are more friendly towards us. Previously restrained, they talk to us more freely.

Looking over the railing of the upper deck into the sea I notice how the ship changes its course frequently, apparently to avoid any German submarines which could be in the waters. I point this out to a man standing next to me and he asks ''Have you been interned in England?" Rather astonished at this question I relate to him the story of how I was taken from my place of work, told that it would only be for a few hours and being here on the ship with just my suit, two shirts and two pants, my-only possessions. All was left behind on that farm.

With a wry smile this man turns towards me and says "Look at me, I have not even got that! Just this shirt and trousers and glad to be alive!" And then he gives an account of his situation and how he came to be here:

In 1933 when Hitler came to power, being Jewish he was sent to the concentration camp in Dachau but was lucky to be freed in 1935. Then he left for Belgium where he hoped to settle, but in 1939 war broke out, Belgium was occupied by the Nazis and he found himself on the move again. There were parachute troops everywhere and bombs, shells and grenades. Masses of people fled to the French border and everybody made for the seashore. A few potatoes and a small amount of tea was all they had.

French soldiers with fixed bayonets accompanied the stream of refugees. For the soldiers they were just Germans who had to be shot. A friend of his, exhausted from the never-ending march, stayed behind. A shot - and he lay there forever. On went the march. His little case became too heavy for him and he abandoned it in the nearby ditch. His feet were aching and began to swell, and still he went on. The French soldiers fired indiscriminately in all directions, forgetting that they themselves were also refugees.

They reached Dunkirk. A cruiser! Exhausted they reached Dover in England. Examinations followed with imprisonment, selection, tribunals - internment. Being Jewish he was classed as a "friendly alien" and sent to the Huyton Internment Camp, and now on this boat.

I listen to this man's sad tale and who actually feels happy to be here, alive. I bend my head over the railing and look into the foamy frothy sea.

On the eighth day there is great excitement. In the distance a small strip of land becomes visible, mountains, hills, even buildings. Then it disappears again, only to emerge after a short while from the waves of the sea like a mirage.

Rumour has it that the 'Arandora Star’[3], a ship with a number of German prisoners-of-war and also many internees, mostly Italians, was sunk by a German submarine, and there seems to be only a few survivors[4]. It was the ship that preceded our departure from Huyton and on it were many Italians who lived practically all their lives in England, mostly in London. They never became naturalized, and under the emergency measures were rounded up and interned. Soldiers and officers confirm the truth of the report, and suddenly one becomes aware of the dangers we have been exposed to.

Like a picture on the horizon the landstrip becomes visible again, getting brighter and larger. Green hills and mountains rising in the background, villages, streets, railway lines. People can now be seen - it is CANADA! The ship, floating along in the St. Laurence River, is now accompanied by a pilot- and police boat. We approach and dock in the harbour of Quebec!

The first groups of prisoners-of-war have already disembarked and stand assembled on the quay, making their exit under heavy guard. The group from the Isle of Man follows and at last it is our turn. The English soldiers on our ship wave good bye, and we find ourselves flanked with fixed bayonets by the Canadian guards of the tank corps with their shorts and black berets and stern expressions.

Our luggage has already been transferred to the waiting train. Another medical examination is carried out before we can mount the railway carriages. The atmosphere among the groups in the compartments is tense and subdued with the thought of the drowned refugees of the Arandora Star still uppermost in our minds.

We made it! We got here! This is Canada! But why the cordon of the Canadian tank corps? On their part they are convinced that we are dangerous Nazi-Germans. "They wouldn't have sent you over here if that wasn't the case", they tell us, not believing or understanding that there are also 'friendly aliens'. All doors of the toilets in that train have been removed. Could it be fear of escape?

Everybody is issued with a box containing bread, sausages, cheese, butter and various tins of food to last four meals. There is hot tea and biscuits as well. Everyone seems to be tired but content. Somehow I don't feel well and then fall asleep. The noise of the engine with its big bell on top keeps me half awake - ding dong, ding dong. The train comes to a halt.

Fully awake now I can see the sun just rising on the horizon at the dawn of the morning. Through forests and wealds the train winds its way along. 'Defense de fumer', a French sign in big letters on a tree becomes visible. This is the French province of Canada - Quebec, larger than Germany. No habitation to be seen, just forests - trees, trees and more trees.

I wonder where Franz was taken to? People are gathering curiously as the train passes a station, and the continuous ringing of the huge bell penetrates the atmosphere as if to shout; Here are the Europeans, Nazis, War Prisoners! Come and look!

With increased speed the train continues its journey through the vast forests, lakes, hills, mountains and small villages. With a sudden jerk it stops at a larger station looking like a railway junction. On the platform people are waiting, probably for their trains. The station's name plate of this small town. has been covered up, apparently to prevent the prisoners to know their whereabouts. As we move on again, on a road signpost the name "Cochrane" becomes visible.

Sunday, 14th July at 7 o'clock in the evening Canadian time, we approach a place surrounded by about 50 tents, a large building and some wooden huts in the background. One of the other side of the track you can see the local village with its farm cottages. A few people are looking on as the train comes to a full stop. This is Monteith[5], in Northern Ontario, Camp Q[6].

The first impression of the building with its great windows secured and fenced with thick iron bars and the small space in front of it, is one of dismay and dejection. Here we are in Canada and we read with astonishment the notice placed on the building: “This is a Prisoner-of-War Camp”. Someone says: “This is Sing Sing”.

Bedsteads are put up and for 250 refugees it is retreat into tents on the grass verge in front of the building. It is 3 o’clock in the morning before everybody is settled somewhere. The sergeant major, somewhat intoxicated, bellows: “Prisoners, I tell you, behave yourselves! Prisoners do not make trouble! Prisoners read the regulations. I don’t wish you good night because I don’t want to”. He then slams the door noisily and turns the key. Everybody is too tired to take any notice of all this.

The luggage is still in store and kept there to be examined before we can receive it.

Next morning we can see the came in daylight. We find the house to be a recently built prison intended as a transfer camp for state prisoners with good behaviour who are also to work on the adjacent farm. This prison is in effect a modern building we’ve all amenities: central heating, showers, a spacious dining room, a modern kitchen and stores. The rations are generous and plentiful, there are is real butter, real coffee, and the meals compare well with any one finds in good restaurants.

The toilets have no doors and there is no privacy. The wash basins are placed opposite and with the large mirrors in front of them it doesn’t make a good sight. With the luggage still kept in store and in the absence of soap and towels, washing at this stage is not very satisfactory.

The grounds are not very large and gradually one becomes more accustomed to be the area after some exploration. Behind the barbed wire fence with its watch towers the landscape stretches over a railroad, a highway, some buildings, farmland with cattle and horses, and all this moulds itself into a beautiful picture. Apparently this place has a semi-tropical climate with a hot sun, and a warning is given by the medical officer not to sunbathe for any length of time, avoiding sunburns which could be painful and dangerous.

Elected representatives trying to explain to the Camp Commander what our position here is. We have a roll call and on the grass verge in front of the building everybody has to strip naked and is examined by the M.O. anc our clothing is searched. At last all belongings and luggage are returned.

A man in civilian clothes, sitting next to the officers at the table, announces that he is an interpreter. “Ich bin Ihr Dollmatch” (I am your interpreter), he says in German but is immediately shouted down. “We don’t need an interpreter, we are not prisoners of war, we are friendly aliens who have been sent here. We all speak good English. Now, sit down!” The officers find this somewhat embarrassing and conduct their business as if nothing has happened

We have our belongings returned again and can sort things out a bit. Eric, Paul, Karl and I occupy a medium-large tent and we settle down, trying to make ourselves as comfortable as possible. We soon build a make-shift table out of scrap wood and it is even praised and admired by the officers at inspection time.

The following day our representative are summoned to the captain and. introduced to the Swiss Consul who is offering his services as a 'mediator'. “We don’t need the Swiss Consul”, our representatives exclaim, “ours is a Refugee Status and what we want is to be free and go to England to assist the war effort against Hitler. We have nothing whatsoever to do with Germany and it's Nazi regime". The captain just cannot understand. how and why these 'darned' internees want to reject the help of the Swiss Consul. But, of course, he is ignorant of all the facts and does not know that the Swiss Consul here is in effect the lackey of the German government.

In the meantime the first bombs have been dropped on London and the Battle of Britain has begun in earnest. And we are here in Canada behind barbed wire. Perhaps we should be pleased to be safe and not complain? We find that hard to swallow. Rumours have it that the transport following our departure from Huyton was sent to Australia. So there is nothing for it but to settle down to this camp-life and make the most of it.

Outside, on the other side of the fence, the soldiers of the Canadian Tank Corps are assembled, and we sing our English songs, and soon a kind of bond is established. They in turn bombard us with cigarettes and chocolate over the fence, and there are smiles all round.

A gala evening has been organised and the Camp Commander has been invited. The large dining hall has been converted into a playhouse, a little theatre with a stage and curtains is erected, and soon the sounds of the camp songs, composed by the internees to the accompaniment of their own orchestra, fills the whole hall and camp:

You'll get used to it, you'll get used to it.

The first year is the worst year.

You'll get used to it.

You can scream and you can shout,

They will never let you out.

You'll get used to it.

It serves you right you so and so

Why weren't you a naturalized Eskimo.

Just tell yourself 'it's marvellous!'

You get to like it more and more

And when you are used to it

You feel just as lousy as you did before.

The Camp Commander, the adjutant, the S.M., the M.O., they are all here listening and seemingly enjoying the performance.

The talented painters in our midst have staged an exhibition of caricatures of all the officers which is well received and applauded.

The soldiers of the Canadian Tank Corps are now replaced by the Canadian Home Guard. We are all assembled along the fence waving farewell to the departing soldiers.

One wouldn't think that conditions such as ours could be conducive to a vision of all our ideas of the past and to the construction of new ideas for the future. To a limited extent this is so. The energetic minority, capable of connected thought and sufficiently intelligent for such difficult tasks manage to occupy their time usefully. They fill every spare minute, and there are many who, with a persistent effort to reform themselves, plan the 'new world'. They are not wasting their time, and internment may even prove a boon for them.

This has brought the formation of a camp school with lectures and the possibility of further education and later on lead to more specialized studies. Such lectures in all fields from agriculture and other practical studies to education in the wider sense are, with the help of the experienced brains and teachers among us, to provide opportunities for all, young and old, with some kind of success.

Soon the Camp University with its groups studying English, French, Spanish, Mathematics etc. is in full swing.

Somehow a football turns up, goal posts are erected and the formation of various sport teams is going ahead.

Musical evenings are held with not only songs but classical music from Chopin to modern dance music, from the 19th century drawing room to the 20th century night club, have become regular features.

Everybody has become reconciled to their present fate and they want to make the best of it.

Canadian newspapers are in circulation. From them we learn that the question of the 'friendly aliens’ was raised in the Houses of Parliament in London at Westminster, and it was even stressed that people who were already serving the country in their war effort have been interned and shipped overseas. Notwithstanding the facts, it is with astonishment that we came upon a paragraph in the paper which emphasized that the consignment of aliens recently sent to Canada consisted of notorious and most dangerous German prisoners-of-war.

It is futile to protest, and perhaps the officers themselves have a good laugh and some enjoyment out of it.

The gates are opened and we are sorted out into groups. We are actually going to work outside the camp, mainly on the land, for which we will be paid. We will be able to buy chocolate, toothpaste and other luxuries in the recently formed canteen.

Our civilian clothes are taken from us and P.O.W. outfit is issued: blue trousers with a red stripe down the right leg, blue jackets with a red circular patch across the whole back, and also shoes and underclothing. "A musical comedy dress”, said an English officer.

Photographs and fingerprints of all internees are taken. Below the heading 'Offence', the fingerprint record sheets carry the entry: 'Interned Refugee'. But officially we are still classed as 'Prisoners-of-War - Second Class'.

At last the British Government has issued a White Paper on the refugee problem and the release from internment of those would be able to do some useful war work, on farms, students whose schooling was interrupted to continue their studies etc.

Application for this release is again made and sent to the Home Office. One of the internees is called before the Camp Commandant and told that his release has come through and that he is accepted for the Czech Army. However, it turns out to be only a theoretical release; in effect, he is still to be interned in this camp - and to wear the same P.O.W. outfit.

A letter arrives from the Committee confirming that application for release has now been made on my behalf. How much longer is it to be?

A censored letter reaches me from my father in Prague. Evidently they are still free and my mother is anxious to hear from me. The news are not good - people in Prague have been rounded up and sent to the concentration camps. As this letter took three months to reach me I wonder what has really happened. With my eyes closed I am lying on the grass, smiling. Only yesterday the Camp Commander remarked.: "You are lying in the tents like black snakes on the rock". Another wise-crack of his: "You are walking about scribbling in little note books and reading books, like in a kindergarten”.

My thoughts go back to my childhood and youth, back to Vienna and Czechoslovakia.

I was born in Slovakia. My grandparents lived there, and when my mother's confinement was near she travelled from Vienna to the village of Lubina where she was brought up as a child, to be with her parents in her hour of labour Lubina was a small, village, the nearest town was Nove Mesto nad Vahom (New Town on the river Waag), also called by the Hungarian name of Vaguhawl. It was in the Hungarian part of the country, and it all belonged to the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. My mother was brought up there and went to a Hungarian school.

The year was 1915 and the First World War was on. My mother told me the doctor gave me just 48 hours to live, but my grandmother nursed me and proved him wrong.

I don't remember the very early years until we were back in Vienna when the war had just ended. Slovakia became part of the newly formed state of Czechoslovakia and Austria became a republic. I am on holiday, walking down the market in Nove Mesto with my grandfather. "This is my grandson from Vienna", he says to the friends and acquaintances we meet. Back in Vienna again - schooldays, afternoons at the 'Kinderfreunde' retreat where I get help with school home-work, growing up, joining the socialist youth movement and taking part in its political activities.

At weekends we wander through the Vienna Woods and in the scout movement we go camping, We train to fight the threatening reactionary forces of Clericalism and Nazi Fascism.

I leave the middle-school to join the workforce and become an apprentice in a printing firm, and I also join the trade union and become an active member. The reactionary forces of Fascism show their evil face and destroy democracy; parliament is dissolved, dictatorship is governing the country. We work in the underground movement under constant threat of arrest or being sent to concentration camps.

Hitler has come to power in Germany. I leave Vienna with my parents for Prague, and after Austria has been invaded by Nazi Germany and now Czechoslovakia taken, I find myself in England.

I wake up with a start, at first not knowing where I am after the reminiscent vein.

Evening has come again and fascinated, by the rich orange cloud in the sky I look up to witness the aurora of the northern lights with their luminous meteoric phenomenon in a tremulous notion circulating the horizon.

The date is October 1940 and the Canadian internment authorities have decided that there should be a separation of Gentiles and Jews and there are to be three kinds of camps for the interned refugees from Nazi Germany: One camp for Gentiles, two for liberal Jews and one for orthodox Jews.

The execution of these measures does not prove an easy task for the authorities who are not particularly well versed in such subtle distinctions. In the process of selection, the lines of demarcation get somewhat blurred. Friends who have met during internment want to stay together, without consideration for their racial ancestry, and harassed camp commandants are unable to obtain an authoritative interpretation of the terms 'Jews' and 'Gentiles’ from Ottawa.

The Nazi-Nuernberg laws can hardly be applied, and in the end the spokesmen for the internees receive orders to supply so many Gentiles, so many liberal Jews and so many orthodox Jews to make up the required numbers. There are to be a camp 'A', a camp 'B' and a camp 'N' and 'I'. Camp Q was to remain a camp for Nazi prisoners-of-war, loyal to Germany. A month ago a sentry said: "You won’t be staying long here, boys, we want the German sailors to freeze here". It turns out to be right.

I am selected for camp ‘I’. Unfortunately Eric, Paul and Karl are selected for different camps and again we are to be separated. The box furniture we made, the simple tables and chairs out of scrap wood are put on a heap and. burnt , A farewell party is arranged with a huge cake, a camp- fair and a last sketch with witty descriptions of the happenings and the habits of various people during our stay in Camp Q.

What will tomorrow bring? Will the new camp be better? Will there be work or is it a step towards the final release? In any event, tomorrow we shall be sitting in the train again travelling ten, twenty or thirty hours towards the unknown.

Tuesday, December 31st 1940.

It is already two and a half months since we left Camp Q and today, at the end of the year, the hundred of us have integrated well with the existing community of other refugees in Camp I.

Indeed as we thought, we travelled down here in the train guarded by soldiers, with doors removed from the toilets and windows just opened wide enough to get air in. Everyone was issued with a bag containing bread, sardines and cheese, the ration for· our- journey.

The farewell from Camp Q at the tiny station still lingers in our minds when officers and soldiers, the Camp Commandant and the inhabitants of the village stood at the railway station to see us off.

Again we wonder what our destination will, be as we roll through the Canadian landscape. The sun has already set and it is dark when the train passes through Ottawa . “Over there is the parliament”, says a soldier pointing towards a building, but it is too dark to see it and. everybody is soon asleep as the train races through the night.

Dawn is approaching as we wake up and in the morning twilight we can see buildings, streets, a. tram going by, cars, and we are in Quebec’s capital, Montreal. But the train continues through villages and small towns, across the bridge over the St. Laurence river.

French signposts of St. John, St. Paul, St. Valentine show us where we are before the train comes to a halt. There are buses and people are gathered round. Just as. they were up in Monteith - "Here they are, more prisoners-of-war". We get off the train and an interpreter stands there: "Schnell schnell", he says in German, “Wen wir sagen schnell, wir meinen schnell “. Every body laughs.

A five minute ride on a bus brings us to the quay of a river and we are then transferred to ferries taking us to the island of "Ile aux Noix " in the river Richelieu , "Well at least there can't be any barbed wire fence", says someone. This thought is soon dispelled when, after another ten minute walk, we notice the wire fence surrounding a kind of fortress and we enter a large gate with the inscription: FORT LENNOX[7]. Inside there is a square, a three strained barbed wire fence with four watch towers and a large building with thick walls and small windows - a prison.

We become aware of the other internees who have been her for three months. Attached to the gate is a large notice in German:

IMPORTANT NOTICE - - STRICTLY FORBIDDEN. THIS TERRITORY BETWEEN THE BARBED WIRES WHICH SURROUNDS THE INNER ZONE OF THE CAMP, AS WELL AS THE OUTER ZONE, IS FOR THE PRISONERS-OF-WAR OF THIS CONCENTRATION CAMP STRICTLY FORBIDDEN! THE GUARDS WILL SHOOT AT ANY OF THE PRISONERS FOUND IN THIS TERRITORY.

BY ORDER OF THE COMMANDANT CONCENTRATION CAMP ‘ I’'

This is the exact translation of what was written in badly worded German.

We are led into the building where we can see a large, badly lit room, on the left are tables and benches and to the right wooden partitions with washrooms and the kitchen behind. Again we have to undress and after a shower we are examined by the medical officer. And again they take our few possessions and we are shown to our placings and sleeping quarters.

All the other internees are Jewish refugees who came to England on a transit visa and went to the Kitchener Camp[8] in Sandwich, Kent, before internment and who were also sent to Canada. They tell us that the fortress was in a more dilapidated state than it is now and that they had to work hard to clean it all up. Walls and windows were obscured by cobwebs and bats had made this their headquarters.

The Jews are also 'friendly aliens' but were brought to Canada as 'most dangerous prisoners-of-war'. They too have been robbed of their possessions by the Canadian soldiers and for the last three months their treatment by the camp administration has not been much better than the treatment of the Jews in the German concentration camps. Unlike us in Camp Q they have not had a say in the running of the camp and they have worked very hard indeed to bring the camp up to the present standard. At least we found ours clean.

We hear that our other friends from Camp Q are billeted further up the mainland in a disused locomotive factory, Camp A and Camp N. In the disused railway shed the rails are still there and the floor space is about a quarter less per person than is required in H.M. prisons for sleeping quarters. For the 750 people there they have only six W.C.s and seven water taps which also serve the kitchen. The windows can only be opened with difficulties or not at all, and the floor is partly flooded with waste water.

Apparently there is also another camp on a small island in the St. Laurence river with similar conditions. So in comparison this camp seems to be the better one.

On the walls are fixed large iron ring and we conclude that this must have been barracks for troops where perhaps the soldiers kept their horses. The room here is partitioned to provide house stores, offices and even a small synagogue for the orthodox Jews. There are also rooms above serving as sleeping quarters.

This island is on the river Richelieu, an arm of the St. Laurence river. All rations have to be brought over by ferry boat and this entails a lot of work for the internees.

Gradually things are getting better and more organised and work is distributed so that everyone is doing his share. Cesspools are to be built under the supervision of skilled prisoners, originally engaged in similar work and here have the opportunity to use their experience. The soldiers who still live in tents nearby are to have wooden huts built for them and everything is done in industrious factory fashion.

However, the machine guns are still mounted on the watch-towers and the soldiers, mostly French Canadians, still think of us as prisoners-of-war and also express their dislike of the British.

Taking a little rest after some quite heavy work, a sentry walks over to me and shouts “Don’t hang about, get on with your work!"

"What do you think I am, a criminal?" I shout back “and no prisoner-of-war either!”

He turns with his gun shouldered and just says , "Shut up!"

Another sentry reprimands one of our group and some argument explodes with the words "Come on you fucking Nazi". A complaint is made to the Camp Commander who promises to look into the matter.,

Work is under way and the 20 cents daily payment comes in handy for buying chocolates or cigarettes in the canteen. The soldiers become friendlier and sometimes they give us the extra bit of chocolate or some cigarettes. Occasionally we get into conversation and they tell us about the Canadian scenery, beauty spots and places of interest., They wonder why we were brought to Canada and although not believing our plight, they point out that they too are in a sense 'internees' as they have had to give up their work for this kind of military service.